| |

|

|

March 26, 2013

Inside Thailand's Conflicted Forests

Birding in Phu Jong Nayoi National Park, March 10-13, 2013

My wife, Supeena, and I spent two months travelling in mainland Southeast Asia, three weeks of which we spent birding throughout the west, central and northeast parts of the Thailand. We have birded on trips to Southeast Asia for over a decade. Our last stop on this trip, Phu Jong Nayoi National Park in Ubon Ratchathani Province, provided such an unusual experience that I decided to write this narrative accounting our journey. It is an informal travel essay with links to photographic illustrations from my Flickr photostream, and in it I list all of the bird species that we identified, along with maps and location information that may be useful for birders heading to the park. For bird species, my photos from Phu Jong Nayoi are used when possible, otherwise they were taken elsewhere in Thailand.

Sunday

Bak Teu was a villager living near the area that is now the National Park called Phu Jong Nayoi in the remote southeastern corner of Isan, the Northeast Thai plateau. The park is part of the Dangrek mountains that straddle the border with Cambodia and Laos. An impressive 40m waterfall is host to a number of large beehives hanging from its sandstone cliffs, and Bak Teu sought to get them. He descended along a large vine hanging over the cliff. But he had not made offerings to the local spirits, and when his companions saw the vine they mistook it for a snake and slashed at it in fear. He fell to his death, and ever since the waterfall has been known as Bak Teu. And locals have considered it unlucky and many more have died in its vicinity. While the name of the waterfall has been changed to Huay Luang ("royal brook") to sound more inviting to tourists, the land of Phu Jong Nayoi remains a conflicted ground for humans and nature.

We made a four-day visit to Phu Jong Nayoi for birding and to see the waterfall, expecting our stay to be comparable to our many other visits to Thai national parks—relatively easy, with many good birds, and perhaps some challenging forest hiking. But from the moment we arrived, it became clear that this was not like other parks. Driving into the park on a Sunday afternoon, we found the gate up and the guardhouse empty. The nearby building for park officers was dilapidated, with the roof partially caved in. Proceeding through the open gate, we found the forest to left of the road burned, smoking, and in some spots in flames. We were here at the height of the dry season, during an unfortunate drought that has hit the region.

For many kilometers, the underbrush of the forest burned, and no one was there. Coming from Southern California, seeing an unattended forest fire was startling. We passed a group of local people carrying baskets and in good spirits, and wondered where they were coming from, noting how many kilometers they had to walk back to the nearest village along the road. We arrived at the campground and headquarters, where an officer gave us tickets and directed us to an entirely empty office building. We wandered around until we found another officer who was rather put upon to stop watching muay thai and get us a key to the bungalow that we had rented for three nights. We unpacked and got settled in blazing heat, the atmosphere saturated with smoke and ash, and wondered aloud why no one around us seemed at all concerned.

Higher up the mountain, we found the Huay Luang waterfall, now a mere trickle over a substantial cliff face, and figured that the following morning it should be a promising spot for birding. An officer nearby informed us that there were not really any trails for hiking, just one "nature trail" that was one kilometer long, and he recommended against walking it because there were too many cobras. The bite of a Thai King Cobra (ngu jong ang) is extremely lethal, and can kill a human in 15 minutes. We had already come face-to-face with a cobra a few weeks earlier, when one approached our birding blind deep in the forest near Kaeng Krachan National Park, and that was enough for a lifetime. It was neither shy, nor more afraid of us than we were of it. We were reaching a point of despair, thinking we would spend three days birding from a single spot overlooking a waterfall that was now barely a trickle, breathing the smoke from an out-of-control forest fire. Then we hear a series of gunshots, from down the canyon less than a kilometer away.

We found a senior officer who says to meet him tomorrow morning and he'll take us to some places where he sees birds regularly. This is wonderful news to us! When we were beginning birders visiting Kaeng Krachan National Park a decade ago, when it was well-known but rarely visited, a similar promise from a park official resulted in a fantastic multi-day tour of extraordinary wildlife. And we also learned from this officer, Mr. Manit, that the fire burning through the forest was not an accident. He suspected that local villagers set fire to the forest along the road, and then captured and hunted the fleeing animals, for food and for sale in local markets. What began for us was a fascinating journey into the conflicts between people, animals, the environment, politics and government playing out in one of Thailand's most remote corners.

Monday

The night was difficult. Before dinner, we had poked around the campground and found many common species of birds, such as Large-billed Crow, Greater Racket-tailed Drongo, Asian Barred Owlet, and Green-billed Malkoha, and were relieved that despite the fire that seemed to be burning all around us, there was still more life than we had found during our recent visit to the Khouang Si waterfall in Northern Laos, where excellent habitat was almost devoid of birds, presumably as a result of extreme pressure from hunting and trapping. But in the dark, the cabin was roasting, the air was still and thick with smoke, and the cheap three-speed fan offered only three variations of low.

Waking to the call of a Red Junglefowl, we head to the waterfall before 7 a.m., and are thrilled that the first bird we see is a Pin-tailed Parrotfinch, a scarce and local specialty that we had missed at Kaeng Krachan and did not expect to see anywhere else. They specialize on young bamboo seed, and travel widely to find their favored food. As a result, they roam widely and cannot be reliably found in any one location, and are thus a prize for birders. The hillside below us is full of flowering bamboo, and has attracted one pair of Parrotfinch, green finches with blue cheeks and a brilliant red tail, along with flocks of common White-rumped Munia. In the trees above us and down the hillside we find Grey-eyed, Puff-throated, Stripe-throated and Black-crested Bulbuls, Dark-necked Tailorbird, Ruby-cheeked Sunbird, Ashy Drongo, and calling from across the canyon an Oriental Hobby—a small falcon with a rich rufous breast. A Little Heron forages along the river below the falls, and Blue-eared Barbets call from atop the canopy, providing percussive duets that accompany the duration of our visit. We also spot a reddish Finlayson's Squirrel with a white ring of fur around its tail. Our host is over an hour late, so we abandon the waterfall and drive a kilometer back to a dirt road leading to Kaeng Kalao, a rocky area of the river feeding the waterfall that becomes rapids in the wet season. Passing fallen trees still in flames, we figure that a wide dirt road would be relatively safe from cobras. Sounds along the road suggest that many ground-dwelling species are present, but they remain entirely out of sight, always hearing us and disappearing before we can see them. But the river, now just a few small streams over a wide expanse of polished sandstone, is promising. A Grey Wagtail forages along a small side stream and a Taiga Flycatcher sallies from the trees. A vibrant green and brick-red Emerald Dove comes to drink from the water—beautifully illuminated but too far to photograph, and Supeena finds a Common Green Magpie. There are also large numbers of butterflies, rivaling the number and diversity that we had observed along forest trails in Kaeng Krachan National Park.

We return to the waterfall and to find our guide, Manit, waiting for us. With nothing more to say than "are you ready?" he leads us down a short trail and into a narrow cave. I wonder to myself what had happened to his admonition about cobras as I squeeze between cool rocks barely wide enough for a person to pass, trying not to bounce my camera or binoculars off of the sides. Emerging on the other side, we follow Manit as he deftly scales rocks and brushes aside understory vegetation. He has bought us to the rim of the waterfall, an extraordinary vista available during the dry season, and also where Bak Teu had met his demise. A troupe of Northern Pigtail Macaques crashes through the bamboo on the far side of the waterfall, and Manit makes sucking sounds with his lips to attract their attention. He then leads us up river, sometimes along the bare rocks and other times up onto the jungle-covered shore where we seem to follow a trail that visible only to him. He moves effortlessly as we struggle to keep up with him, and Supeena points out the he is wearing only flip-flops. And all along he delivers a monologue about the plants, insects, birds and other wildlife, his history with the CIA in the region, and the tension between the local residents and the park.

Phu Jong Nayoi was established in 1983 to protect some of the last remaining forest in Isan and the Dangrek range, and is important also because of the intensity of deforestation in neighboring Laos and Cambodia. But like almost all other Thai National Parks, when the park was created, the people already living within park boundaries were allowed to stay. The government’s restrictions against hunting and burning theoretically put a lock on what had traditionally been their kitchen and livelihood, so many still resent the park. They burn the forest understory during the dry season and they hunt and gather forest products throughout the year, and they clear areas for cultivating crops. The park is 686 square kilometers in size and the few rangers don't have the resources to stop the villagers. Yesterday, Manit called the head park ranger about the gunshots, and they called the district head who should have sent the police to find the hunters. But the police are not trained or equipped for pursuing armed and experienced forest hunters, and so they most likely declined to respond. Catching someone burning the forest is almost impossible; when questioned by rangers, villagers simply claim that they saw a fire and came to collect wildlife. Although even this is illegal, the police are not involved. Like Manit, all but the highest level of staff was hired locally. They know the villagers and while not necessarily aiding and abetting their poaching, they are inclined not to incite and unresolvable conflict and look the other way.

As we continue up the river, eventually looping back to the waterfall via the "nature trail", Manit's rapid pace and ongoing monologue is making it tricky to find good birds. Nonetheless, we add a male Siberian Blue Robin, Black Drongo and Black-headed Bulbul. He has seen Pittas in the rainy season, and tells us that when there is more water, the birding is much better. We find noisy and impatient White-bellied Erpornis, and a number of other common species including White-rumped Shama, Black-naped Monarch, and Grey-headed Canary Flycatcher, the latter two species seeming to appear together every time we see them during this trip. And there is a Blue Whistlingthrush, a bird he calls "kaa naam" or "water crow", but the recognized Thai name is Ieng Tham, which translates as "cave myna". The highlight of the afternoon is a Hainan Blue Flycatcher that flushes from the trail as we pass. The number of birds is quite low, due to the fires and the dry season, but the habitat looks good and the diversity is promising.

From our starting point at the waterfall overlook, Manit leads us down to the pool at the bottom, which is the one of the only places where the Thai tourists go. At a mid-story promontory, we can view the many large beehives that tempted Bak Teu to his fate, as well as an Oriental Hobby nest and a pair perched nearby in a tree. We ended up observing more raptors in this park than at any other location we have visited in Thailand, although many were too distant or fleeting to be identified with certainty. Manit leads us downstream, over rocks and through brush, and then once again heading uphill through the forest on a trail even rougher and less apparent than the one before. I am grateful that, at least during this driest moment of the dry season, there are almost no spiders. Everywhere else in Thailand, hiking through the jungle on trails means dividing attention between searching for birds and maintaining a vigilant focus a few feet ahead to avoid walking face-first into one of the tremendous number and variety of spiders, sometimes of frightening size. One of the most widespread and common is the Giant Wood Spider, so large that it has been documented to capture and consume small birds [1]. The largest I have personally seen was about the size of a basketball, and their bite is toxic. But here in Phu Jong, I observe only the Lawn Wolf Spider that builds a dense and easily spotted web on the ground.

This part of Manit's path—I cannot justifiably call it a trail—is silent and leads us directly through a large area that has burned completely through the undergrowth. The fire, or fires, were started many kilometers away along the road, and the villagers didn’t intend to burn such a large area. But once the fire started, it was so dry that it spread rapidly in just one day. We cannot tell how deeply the fire has penetrated away from the road, but if this area is any indication, it may have reached hundreds of meters at least, probably more. There is no fire suppression here, and the park staff has no resources to fight wildfires. Once a fire is started, it continues until it burns itself out. Manit is visibly saddened to see a year's growth destroyed. The larger trees can survive minor fire, and after the first rains the understory will begin to grow back. In fact, it may represent a kind of sustainable practice that facilitates human habitation in forested areas that made sense in a pre-modern context when forests were widespread. And the traditional Thai view of the forest was as an open-access community resource that could sustain a limited level of exploitation [2].

But the forests that once covered Isan are gone. Those that remain lie along a mountainous arc, broad to the west where it is protected by large parks such as Khao Yai, and more tenuous along the Cambodia and Lao borders. The plateau of Isan that for centuries was sparsely populated land at the margins of surrounding kingdoms has been transformed into an agricultural breadbasket with a vastly higher population density than at any time in history [3]. For decades, the Thai government promoted forest harvesting and conversion into agricultural land before focusing on conservation beginning in the early 1980's [4]. Despite the shift in policy, the government did not widely pursue eviction from state forests, fearing that the displaced would join the Communist Party of Thailand, then a nascent armed insurgency occupying some Northeast forests [5]. Now, paved roads and motorcycles facilitate efficient penetration deep into the little forest that remains, transforming a traditionally sustainable practice into something with much greater destructive potential.

Tuesday

At the peak of the dry season, Thailand burns. Across rural Thailand, small trash fires are commonplace, often including plastics, and cooking fires are everywhere. During the dry season, the stubble from the previous year's rice harvest must be removed to make way for the new planting. The most sustainable practice is to till the soil multiple times, but many farmers opt for the simpler solution of burning the dried stubble and then applying chemical fertilizers. Vistas of scorched earth surrounded us as we drove through central and northeast Thailand. The smoke produced a dull haze that shifted with the weather, and is recognized as a significant seasonal source of air pollution and greenhouse gases [6].

By Tuesday morning, the fire seems to have burned itself out, but on the way to Huay Luang we find the road blocked by a massive burned tree that has fallen. The only large trees that burned are those that had already died, and this one had been just a bare trunk standing alongside the road. After notifying the staff, we park near the road and walk the rest of the way to Kaeng Kalao. We follow the path down the river that Manit has taught us—yesterday it seemed invisible but now we can follow it relatively easily—and add a Green-eared Barbet and Pin-Striped Tit Babbler to our list.

We are anxious to depart this familiar territory and explore some of the other unnamed roads leading into the park from main road 2248. We head for the 'Emerald Triangle', Thailand’s attempt to market the triple boundary with Laos and Cambodia as a tourist destination. The road passes between two large reservoirs, one of which has a shallow bank with a playground and some open land. Here we find an abundance Barn Swallows, as well as juvenile and adult Pied Bushchat, Blue Rock Thrush, Eastern Yellow Wagtail, Plain-backed Sparrow, Little Grebe, Little Egret, Great Egret, Marsh Sandpiper, and Chinese Pond Heron. There are ducks too distant to identify.

The road to the Emerald Triangle passes through thick forest, and has two stream crossings. It is already late and too hot for there to be much activity, but we do see a pair of Black Baza and a Dollarbird—a chunky, turquoise-colored bird named for bright wing-spots that look like coins, but don't really. It is 16km to the border, but at about 14km, the road is blockaded, near the end of another reservoir. Here there is a military base, and a small display commemorating a brutal Thai battle on a nearby hill with the Vietnamese-occupied Cambodian government in the early 1980's. It is hot and quiet, and we can see just an Osprey in the distance. The base appears to be occupied by just a single individual, who eyes us warily from a distance. The border crossing is closed—another consequence of the dispute over Khao Phra Viharn/Preah Vihear between Thailand and Cambodia that flared into a small war in 2008.

For a century, the two countries have contested the land surrounding the Angkor-era temple Preah Vihear built on an escarpment at the edge of the Dangrek mountains. While the temple is just inside Cambodian territory, it is most easily accessed from the Thai side, and an agreement had allowed tourists to visit the temple without formally crossing the border. Over time, a village of Thais serving the tourist market had formed, also on the Cambodian side. In 2008, Cambodia successfully listed Prasat Preah Vihear as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, setting in motion a theatrically politicized conflict over the precise location of the border around the temple and in other places in the Dangrek mountains. This quickly evolved into a shooting war with skirmishes between 2008 and 2011, many troops killed on both sides, and villages and schools near the border burned and bombed by mortars, rockets and even cluster bombs. Making the situation worse for soldiers and wildlife alike are landmines along the border between 1985 and 1989 by the People’s Republic of Kampuchea, placed in order to prevent re-invasion by the Khmer Rouge. They were placed with the unbelievable density of 3000 mines per kilometer, along narrow deforested strip stretching nearly the entire length of the border. The mines remain to be cleared, and have caused many of the casualties of the current border war.

Things have cooled since the election of Thai Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, but the formal dispute still exists and troops remain emplaced on both sides. Throughout the southern half of Ubon and Sisaket provinces, the grounds of schools and temples now host makeshift bomb shelters consisting of segments of large-diameter concrete sewer pipe buried under earth mounds. The temple itself is now open to tourists but only from the Cambodian side. On the Thai side, the National Park is open up to the office and the adjacent mountain overlook called Pha Mau-I-Daeng, but the road to the temple is blockaded. Thai soldiers have erected camouflaged structures and sandbag fortresses, behind a towering Thai flag, and monitor the Cambodian side. Barbed wire is everywhere, and past a certain point, photography is prohibited so Thai positions are not revealed. A few days earlier, we walked up to the front line to see the temple, less than a kilometer distant. The park advertises some promising birding sites, but all are now inaccessible due to the conflict. From the cliffs below Pha Mau-I-Daeng we saw two Dusky Crag Martins.

We return to find the park in the afternoon to find it bustling with activity. The guardhouse is occupied and the gate is down, and we are questioned as to why we are there. Meanwhile, villagers are streaming in on trucks and motorcycles. The campground has been transformed into a community center, and hundreds of people are gathering around a large sound system that is playing lam sing, the regional Lao popular music. We suspect it concerns either the fire, or the visit of a Royal Princess whose motorcade will pass by the park entrance in a few days requiring every town to line the road with flags and honorary signs. Despite our curiosity, we surmise that our presence—especially my presence as a white foreigner—would be too conspicuous and disruptive so we rejoin Manit at the waterfall and hope to learn more later.

He leads us further along the nature trail than we had gone yesterday, to a water catchment where noisy water pumps supply water to the park. The catchment is also an attractive watering hole for animals and Manit points out the well-worn paths where wild boar come to drink. He searches for the footprint of a wild gaur (krathing). These migrate to the park from Cambodia during the wet season, but this year one has come early. The villagers know about it, and have been hunting it for a month. Catching a large mammal such as this would be a financial windfall. Manit finds no tracks. Perhaps if it is stealthy enough, it will survive into the wet season. A closely-related species, the kouprey, is endemic to the area just southeast of Phu Jong Nayoi, in Cambodia and Laos, and was discovered in 1937. It has not been seen in the wild since the 1980's and has likely gone extinct due to hunting and warfare.

We learn from Manit that the large meeting at the campground is a regularly scheduled meeting between park officials and the five hundred local citizens who are registered as residing within the park territory. These are people who lived on the land before the park was created, their descendants, and recent emigrants. This is a common situation in many national parks in Thailand, especially in the north and west, where many upland ethnic groups reside inside parks and sometimes migrate in and out. Human rights advocates seek to protect stateless people and ethnic minorities who receive little to no support from the government, while conservationists are concerned about slash-and-burn agriculture and hunting in diminishing wildlands. The incorporation of forest lands into state control in the twentieth century did not adequately account for the role the forest had played in rural livelihoods, nor were the institutions created empowered to prevent forest encroachment or provide alternative livelihoods [7].

In Kaeng Krachan, Thailand's largest national park, Karen ethnic communities reside in more remote areas of the park where park rangers face off with poaching gangs armed with smuggled weapons from Burma. In 2012, a violent confrontation resulted in a Karen poacher killed while attempting to smuggle a baby elephant [8]. In 2011, Karen residents helped park officials track and arrest a hunting party that included a senior police officers [9] and police have been implicated in ivory smuggling [10].

The dry season is also high season for wildlife poaching, when animals become dependent upon a diminishing number of water sources well-known to hunters. This year, just a few days before we arrived at Phu Jong Nayoi, we saw television reports that two adult elephants had been shot inside Kaeng Krachan. One was wounded and one had died, from bullet wounds from a high-velocity machine gun such as an AK-47 or M-16 [11]. It was found to have been recently pregnant, and it is suspected that a heavily armed poaching gang killed the mother to capture its baby. A baby elephant can fetch $30,000 on the black market where it would end up working for the tourist market, giving performances, jungle rides, or walking the streets of smaller cities for handouts [12]. The story is all over the news as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) conference is taking place in Bangkok, attended by the Thai Prime Minister. Public attention has elicited a rapid response: all entrances and exits to Kaeng Krachan have been sealed, and the Thai Border Patrol Force has been called in to prevent the poachers from escaping into Burma. Some pundits surmise that the poachers have killed the baby elephant in order to escape. It is also possible that corrupt park officials or police have facilitated their escape. The Nation newspaper reports that multiple armed gangs are suspected, including Karen forest residents and local officials [13]. To date, this case remains unresolved.

At Phu Jong Nayoi, there are not distinct ethnic groups nor highly armed poaching gangs, and the park rangers do not carry out the paramilitary duties faced by rangers at Kaeng Krachan. But a low-level tension persists between residents who resent the formation of the park by a government which has done little to nothing to help them, and park officials charged with conserving dwindling wildlands from encroachment, burning and hunting.

Ending the day at Kaeng Kalao, we find Blue-winged Leafbird, Asian Palm Swift, and Fork-tailed Swift. Three Needletails make a rapid pass—they appear to be Brown-backed but don't stay long enough for us to be sure.

Wednesday

A light rain fell overnight providing welcome fire suppression—the air is clean and cool. We stop at the waterfall overlook one last time to get more photographs of the Pin-tailed Parrotfinch. Along the road, the largest fallen logs are still smoldering and smoking, but everything else is damp, and more birds are signing. We leave quickly, wanting to check the river crossings along the road to the Emerald Triangle in the morning hours. We do not see the Baza again, but the river crossings are bustling, and we are thrilled to end our trip with three more lifers, male Purple-throated Sunbird and a female working on a nest, Eurasian Jay, and one Wooly-necked Stork in flight. Also present are Black-headed Bulbul, Greater Coucal, Rufous-fronted Babbler, Greater Racket-tailed Drongo, Asian Koel, Stripe-throated Bulbul, Pin-striped Tit Babbler, a female Picus sp. woodpecker, and many more butterflies.

Phu Chong Nayoi National Park was named after the Mak Chong tree, Malva Nut, Sterculia lychnophora. It’s towering trunks become curiously curvy above a certain height, and the nuts are known for medicinal qualities in China and Southeast Asia. This is the one of the only places in Thailand where the tree grows wild. Locally, the park is still known as "Bak Teu"—a sign of resistance to the central authority that renames and repurposes the land and leaves those living at the margins of Thai society in an ambiguous position.

As we drive towards Ubon, the drizzle becomes a heavy, soaking rain—the first of the season. In a few weeks, fruiting trees around the river will attract flocks of birds and the understory will begin to grow back. Before this trip, we knew that Thailand's National Parks were not subject to the protection that they appear to receive on paper. But witnessing first-hand the complex economic, social, political, and environmental conflicts was sobering. The innovative ecotourist solutions we have seen at heavily-trafficked corridors in Kaeng Krachan and Doi Inthanon National Parks have no viability here. Too few foreign tourists come to this corner of Thailand, and regional residents will not pay a premium to government they distrust for an abstract principle of conservation. The smaller scale of conflict here does not attract the international attention directed towards the devastating levels of elephant poaching in Africa, for example, yet it is serious. Our train back to Bangkok passes alongside the length of the Dangrek mountain range, where, not 48 hours later, a ranger in Pang Sida National Park is killed by a gang of rosewood poachers [14].

Maps

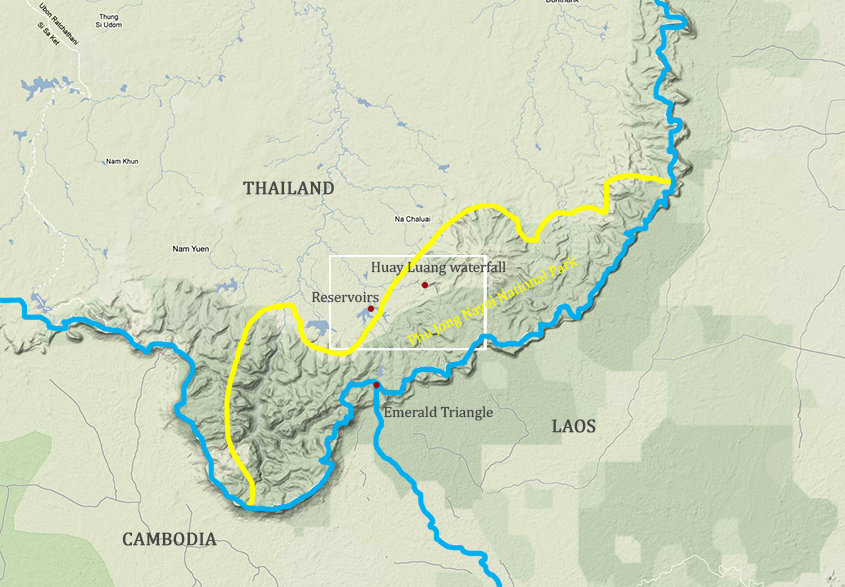

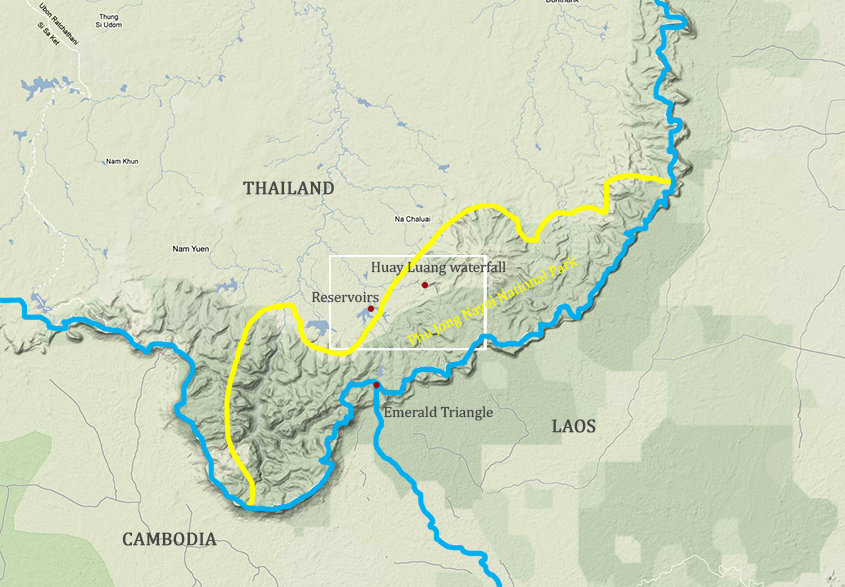

Approximate boundary of Phu Jong Nayoi National Park. Boxed area is shown below.

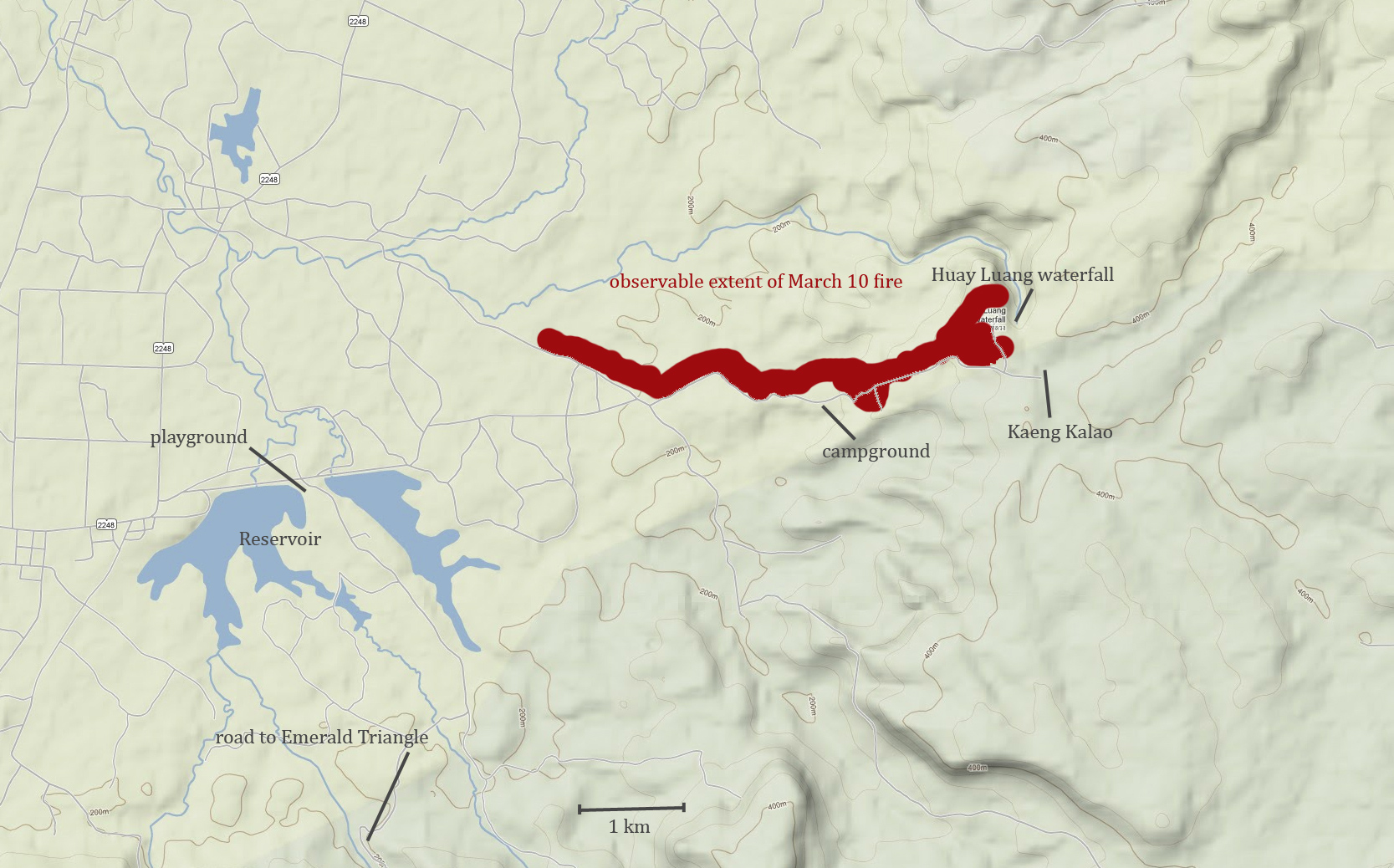

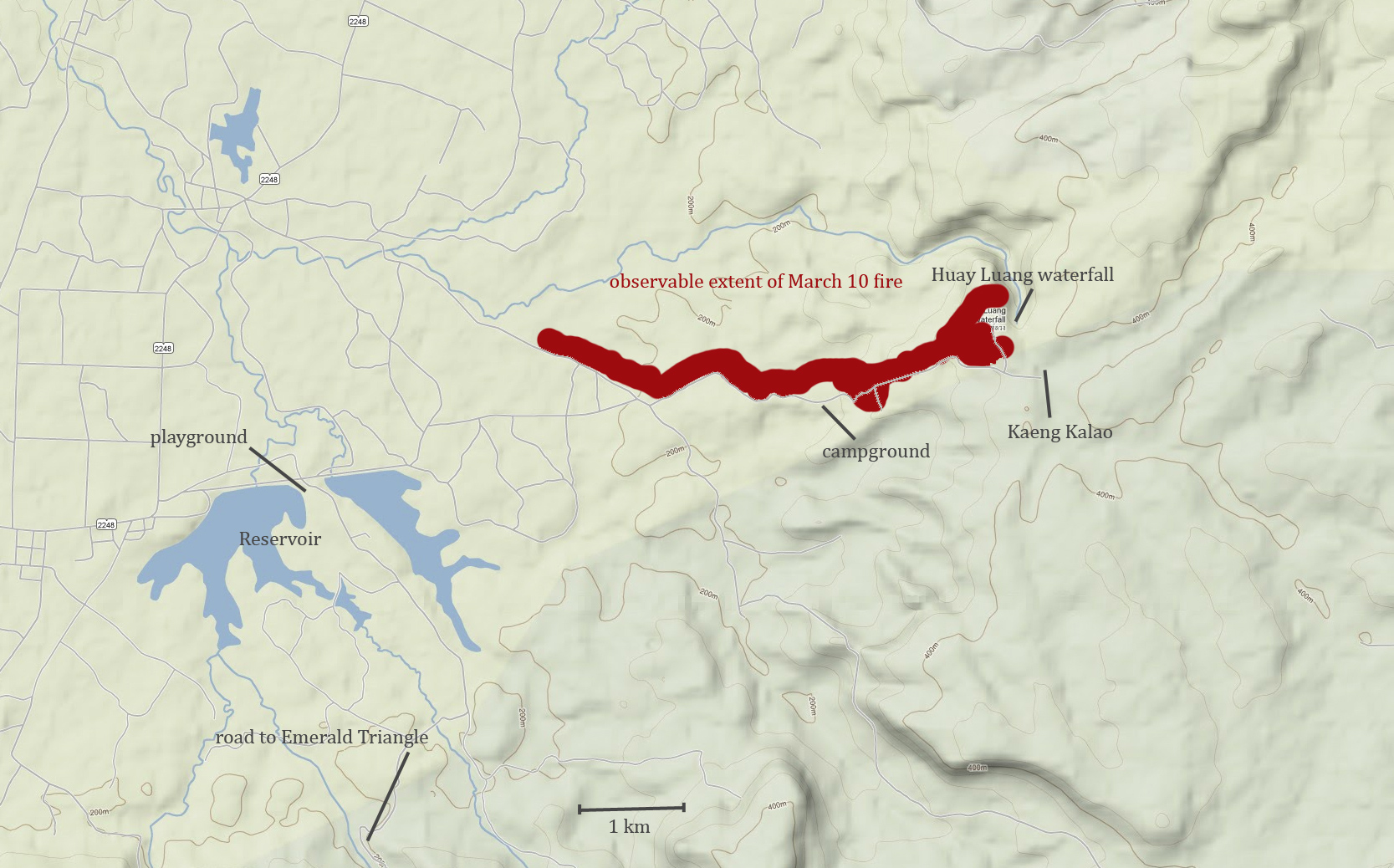

Map of specific sites mentioned in the essay.

Note: Phu Jong Nayoi N.P. is also sometimes spelled Phu Chong Nayoi or Phu Chong Na Yoi.

Sources Cited

[1] Kasambe, Raju, et al. "Recent records of birds trapped in spiders' webs in India." Birding Asia 13 (2010): 82-84.

[2] Rigg, Jonathan. "Forests and Farmers, Lands and Livelihoods, Changing Resource Realities in Thailand." Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters 3:4/6 (1993), 283.

[3] Parnwell, M. J. G. "Development and the Environment: The Case of Northeast Thailand." Journal of Biogeography 15:1 (1988), 203.

[4] Komon Pragtong. "Recent Decentralization Plans of the Royal Forestry Department and its Implications for Forest Management in Thailand." Mekong River Commission publication, 2003. http://www.mekonginfo.org/document/0001346-environment-recent-decentralization-plans-of-the-royal-forest-department-and-its-implications-for-forest-management-in-thailand

[5] Lohmann, Larry. "Land, Power, and Forest Colonization in Thailand." Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters, 3:4/6 (1994), 186.

[6] Gadde B., Bonnet S., Menke C., Garivait S. "Air pollutant emissions from rice straw open field burning in India, Thailand and the Philippines." Environmental Pollution 157: 5 (2009), 1554-8.

[7] Fujita, Wataru. "Dealing with Contradictions: Examining National Forest Reserves in Thailand." Southeast Asian Studies 41:2 (2003), 4.

[8] http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/local/276678/parks-dept-issues-poaching-alert

[9] http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/investigation/335189/shots-in-the-park-threaten-nation-endangered-species

[10] http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/crimes/334077/police-seize-20-elephant-tusks

[11] http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/local/340161/police-hunt-elephant-poachers

[12] http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/local/340306/government-doesn-t-care-about-elephants-say-conservationists

[13] http://www.nationmultimedia.com/national/Crime-gangs-shot-elephant-30201820.html

[14] http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/local/340653/ranger-killed-by-rosewood-poachers

|